AI-Powered Asset Management: From Experimentation…

If it landed tomorrow: Would the water sector survive a sudden shift to Cunliffe-style regulation?

The UK water sector is heading toward a supervisory regulatory model: broader outcomes, deeper scrutiny, more active steering. The shift moves regulation beyond traditional cost benchmarking, toward a wider set of outcomes covering environment, resilience, asset health, and innovation.

Whether a ‘super regulator’ will actually achieve these broader outcomes remains to be seen. The goal, however, is clear: a more holistic and integrated approach to regulation.

Best performance now will not be enough in future. How do the existing upper quartile performers in the water sector fare if recommendations around data mapping, environmental monitoring and asset risk are brought in rapidly? To understand where gaps are likely to emerge, we imagine how water companies would perform if regulated under Ofgem- or Ofcom- style frameworks.

The regulator sets outcomes and steers investment to meet national goals, not just policing price and service obligations. The performance lens is widened to address a range of expectations such as environment, resilience, customer vulnerability, and asset health. Teams would be larger and more multidisciplinary than today, enabling a more holistic assessment of plans, applying a continuous and technical scrutiny that is not possible with the EAs limited resource today. This would be supervisory oversight: a relationship that would blend assurance, challenge, and hands-on steering to meet government targets and public expectations.

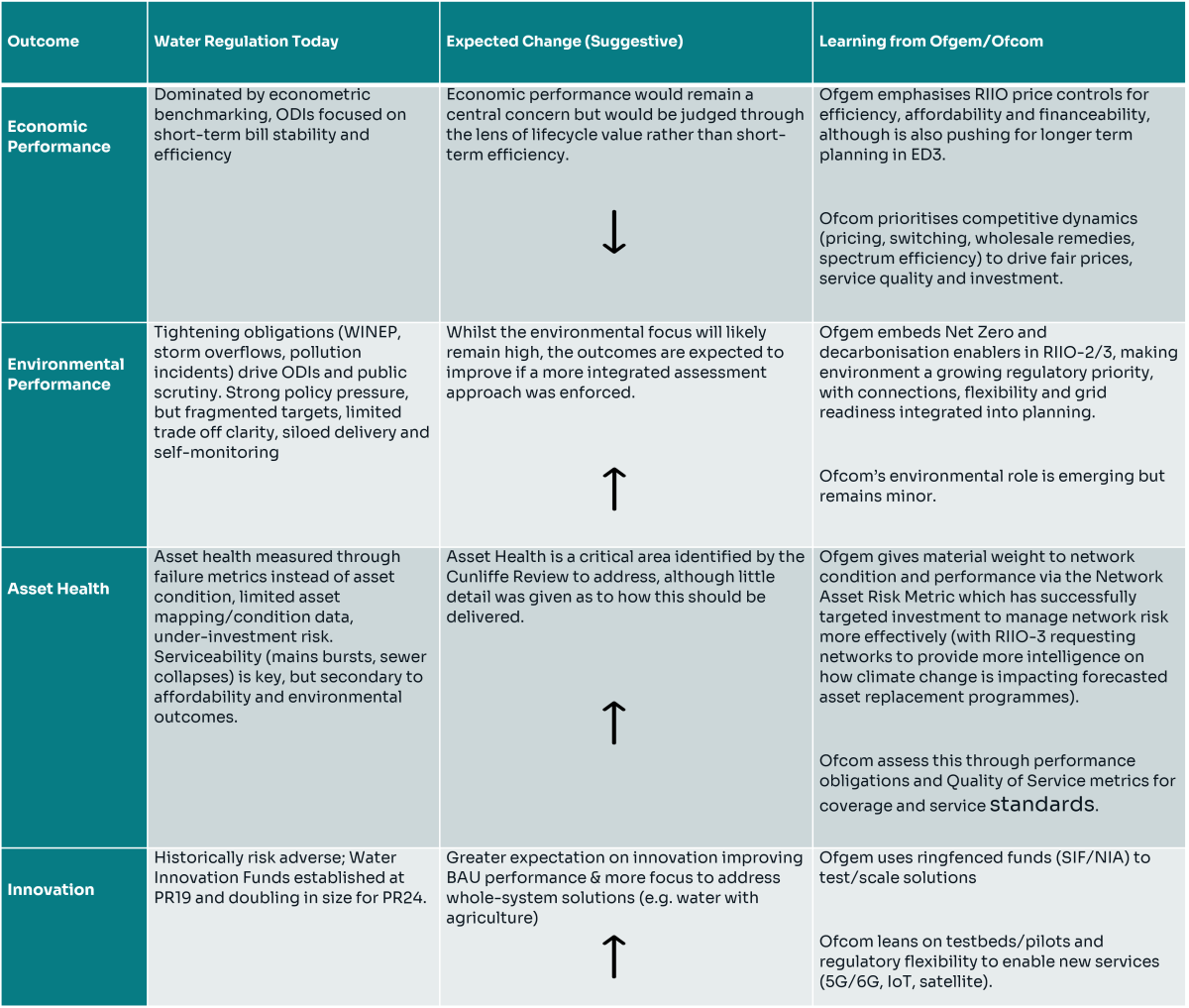

Under a supervisory framework, the regulator would focus more on outcomes, reducing — but not eliminating — the emphasis on econometric benchmarking. The Cunliffe Review findings can be compared to learnings from more energy and telecoms regulation to indicate where focus may shift to under a supervisory framework.

The real shift would be in the capacity of the regulator itself. Supervisory oversight demands frequent engagement and a depth of technical challenge that most water companies have experienced only episodically today. Data pipelines, decision-making frameworks, and internal governance must evolve to support continuous, multidimensional assessment. Landing this right will be crucial to not stifle activities and momentum for water companies.

Even companies that currently outperform on Ofwat’s metrics could stumble under this expanded lens, because the decision making, data and culture that have been optimised to exceed in a cost‑centric regime are not the same as those required for multi‑output supervision. Many organisations today lack the asset condition, and maintenance programmes to deliver against the broader lens. Furthermore, critical datasets (e.g. asset data) are patchy or siloed, and not suitable for consistent monitoring and reporting. Performance gaps are likely to emerge—especially in areas like asset health, resilience and environmental transition readiness.

The expected pace of change is also key. A rapid regulatory pivot can outstrip the practical capacity of supply chains, digital transformation programmes and portfolio governance, creating a situation in which bills rise faster than visible benefits, delivery timelines slip, and public patience thins just as the sector needs legitimacy to invest and innovate. The right pace of change is therefore just as important as the direction of travel.

The Cunliffe review illuminates both the direction of travel and the sector’s readiness gaps. While questions remain about the efficacy of a super regulator and its ability to enhance rather than inhibit planning, the path forward is clear:

Water companies either wait to react to mandates or act now to build supervisory-era capabilities, ensuring they can deliver outcomes for customers, the environment, and society – and maintain public trust.

Partner, Energy and Utilities | London

Scott is a Partner and leads our Energy and Utilities Practice in the UK and Ireland. He is an energy policy and regulation expert with 25 years of experience in market liberalisation, regulatory reform and privatisation.