AI-Powered Asset Management: From Experimentation…

25,000 new CVE vulnerabilities in 2024. Five days to fix the critical ones according to the reference frameworks. The result? Overwhelmed operational teams and frustrated CISOs. What if the problem wasn’t patching faster, but patching better?

In a context where vulnerabilities are multiplying exponentially (with more than 25,000 new CVE entries recorded in 2024), vulnerability management is often presented as the first line of technical defense against cyber threats.

Normative frameworks such as ANSSI, NIST, ISO 27001, and PCI-DSS generally prescribe a strict remediation timeframe, usually five days for critical vulnerabilities.

This requirement contributes to the simplistic idea that any vulnerability not remediated within this period would automatically be considered a case of non-compliance.

However, this confusion between technical vulnerability and regulatory non-compliance can create tension during discussions between operational teams and risk teams.

To begin, let’s define what a vulnerability is and how it differs from a non-compliance.

A vulnerability is a technical weakness in a system, application, or configuration that can be exploited by an attacker to compromise security. It may stem from a software bug, a design flaw, a misconfiguration, or the absence of a patch (for example: the Log4J vulnerability).

A non-compliance, on the other hand, refers to the gap between the actual state of a control and the requirement set by a standard, internal policy, or regulation. It does not necessarily indicate an exploitable flaw, but rather a failure to meet a defined rule. For example:

“The organization should regularly monitor, review, evaluate, and manage changes to the supplier’s information security practices and service delivery.”

(ISO 27002: 5.22 — Monitoring, review, and change management of supplier services)

A vulnerability is not necessarily an exploitable flaw, and an unapplied patch does not automatically mean that the organization is in a state of insecurity. When a vulnerability is published, the timeframe before it is exploited “in the wild” is unpredictable (we could refer here to EPSS, but that would require a dedicated article).

This was clearly illustrated in December 2021 with Log4Shell, a vulnerability in the Apache Log4j library that allowed remote code execution (RCE) — potentially enabling attackers to take control of a server. It was being exploited well before its public disclosure, and its disclosure led to a surge in exploitation attempts.

This dynamic raises questions about the relevance of the commonly imposed five-day regulatory remediation window for critical vulnerabilities.

In practice, operational teams — especially in critical or highly constrained environments (Mainframe, Legacy, OT) — are often faced with the impossibility of applying patches within the imposed deadlines, without risking service interruptions (and therefore business impacts) or technical regressions. This constant tension between regulatory compliance and operational reality raises a question: how and when should we patch?

Meeting remediation deadlines dictated by normative frameworks is an illusion if the vulnerability is not considered within its operational context. Placing the risk of exploiting a vulnerability in the operational context of the impacted asset becomes essential.

So, how can we put the vulnerability and its operational context back at the center of the discussion? Let’s start at the beginning: vulnerability management.

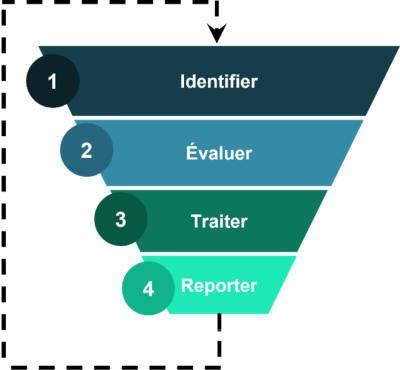

For years, vulnerability management has followed an almost industrial approach, designed as a well-oiled cycle. It begins with identifying vulnerabilities, either through regular scans, bug bounty programs, or when researchers report known (or unknown) flaws on IT/OT assets (this is called disclosure).

Next comes vulnerability assessment, traditionally dominated by CVSS: a number, a severity, a priority ranking. Then comes a comforting illusion: prioritizing “critical” vulnerabilities seems rational. But this model says nothing about the actual risk to the impacted asset, and therefore to the organization.

Then comes the heaviest step: vulnerability treatment, which consists of either patching (remediation) or applying workarounds (mitigation). In the OT world, this is often impossible: updating a PLC or industrial controller can mean stopping a production line. Here, the logic of mass patching is simply inapplicable.

After remediation, the process calls for verification (a pure utopia in practice): confirming that the chosen solution (remediation or mitigation) is effective, that the vulnerability is no longer exploitable, and that exposure is reduced. This step is essential, but in practice, it often reveals the huge gap between what we think has been fixed and what remains exploitable — not to mention potential regressions during version upgrades… A never-ending loop.

Finally, there is the reporting phase. This should be the moment when technical effort is translated into risk indicators that management can understand: “Here’s what we’ve neutralized, here’s what remains at risk, here’s the business impact.” But too often, it is reduced to an infernal count: number of open vulnerabilities, patches applied, patching rate, compliance rate.

This seemingly structured process is now outpaced by reality. Identification produces an unmanageable avalanche of vulnerabilities. Assessment by severity (or by CVSS) misleads more than it clarifies when used alone, without considering the environmental context of the impacted asset. Remediation, when possible, never absorbs the flow of new vulnerabilities. And reporting becomes a dashboard of hollow metrics, far from a real view of risk.

This is where contextualized prioritization becomes the only viable path. It does not eliminate the process; it transforms it. At the identification stage, we no longer collect everything that exists — we prioritize from the start according to the business criticality of the assets concerned. At classification, we abandon the obsession with the CVSS score and cross-check multiple signals: active threats from threat intelligence, external exposure revealed by Attack Surface Management, and the business value of the affected asset. At remediation, we integrate mitigation, accepting that patching is not the only option, especially in OT: we compensate with segmentation, monitoring, and hardening. And in reporting, we no longer present vulnerability volumes, but a risk narrative: “We have neutralized the plausible attack scenarios threatening our critical assets.”

The vulnerability management we once knew is therefore not dead in principle, but in practice. It became trapped in a volume-based logic that no longer makes sense in the face of the growing avalanche of vulnerabilities. Contextualized prioritization does not reinvent the wheel; it restores the process to its original purpose: protecting the business, rather than chasing numbers.

And you — are you still counting vulnerabilities, or are you effectively managing risk?

It’s time to shift from a volume mindset to a value mindset. Your next executive meeting should no longer focus on the number of patches applied, but on the real risks that have been neutralized. This paradigm shift is what will save your operational teams.